Op-Ed

Op-Ed

Active and healthy cities?

No time to read? La Fabrique de la Cité has got you covered. Check our newsletter #54.

To be informed of our upcoming publications, please subscribe to our newsletter and follow our Twitter and LinkedIn accounts.

Find this publication in the project:

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Op-Ed

Death and life of CBD

Op-Ed

Is resilience useful?

Op-Ed

Long live urban density!

Issue brief

Behind the words: Recovery

Op-Ed

Sending out an SOS

Op-Ed

The ideal culprit

Issue brief

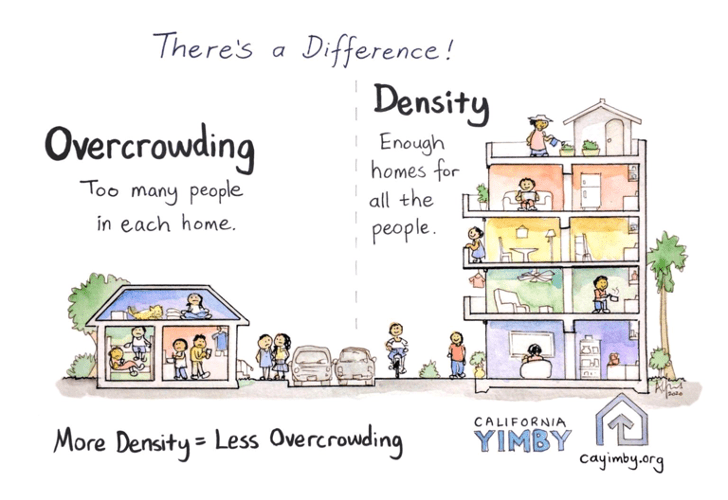

Behind the words: density

Issue brief

Behind the words: telecommuting

Issue brief

Behind the words: urban congestion

Issue brief

Behind the words: food security

Op-Ed

180° Turn

Op-Ed

Cities in safe boot mode

Op-Ed

Across cities in crisis

Op-Ed

A street named desire

Actualité

Resilience: an operational concept?

Expert viewpoint

Zoé Vaillant: health inequalities are rooted in local areas

Expert viewpoint

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger: what role does big data play in cities?

Expert viewpoint

Thomas Madreiter: Vienna and the smart city

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.